If you’re someone who sees philanthropy as investment, we have a tip for you. Invest in community-based organizations (CBOs). They’re undervalued, poised for growth, and can generate remarkable returns.

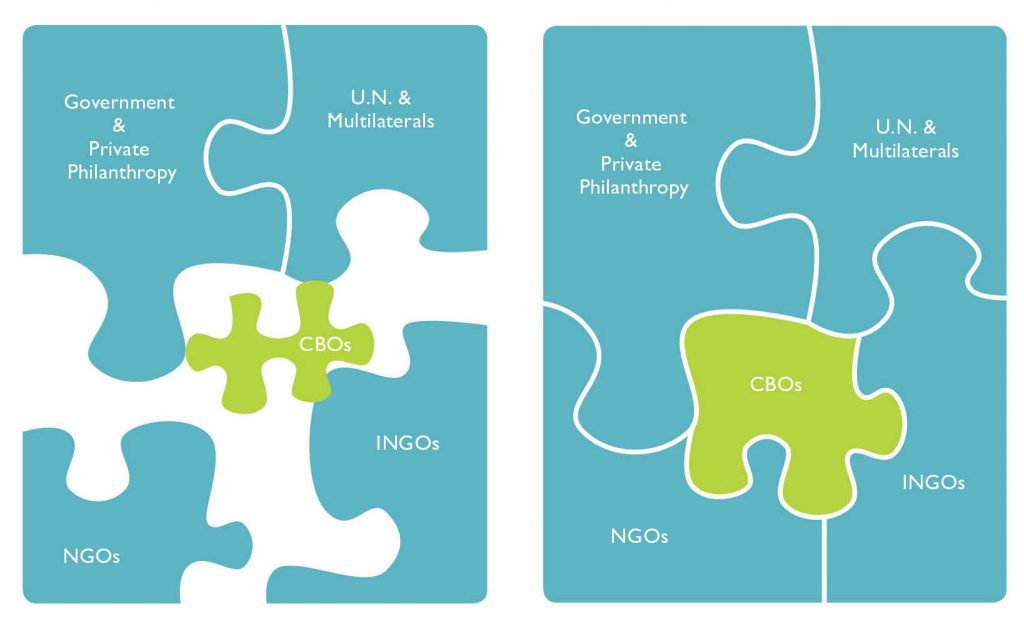

Philanthropists interested in global giving typically turn to well-known international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) or multilaterals like a United Nations agency. In investment parlance, these are (thought to be) low-risk investments. INGOs or global agencies are trusted names who can absorb large amounts of funding. But they employ a top-down model: they either implement programs with their own local infrastructure, or they sub-contract partners at the local level to implement their own strategies and field programs.

This approach has plenty of benefits, like economies of scale. But it’s missing an important element—grassroots passion, knowledge, expertise, and efficiency. Local organizations offer fantastic value for the philanthropist who understands that emerging markets are a growth opportunity.

Community-based organizations are NGOs that work at the local level. They tend to be led and run by community members, and work for the benefit of the community by improving their well-being.

In acting as our clients’ philanthropic advisor, Geneva Global has been working directly with community-based organizations since 1999, granting directly to them on behalf of our clients. We find that local organizations consistently offer tremendous value as innovative, cost-effective partners:

- CBOs already know what is needed within their communities and how best to design and carry out work within the local context.

- Rooted in the communities they serve, CBOs conduct their own development work with infrastructure—staff, operating systems, and relationship networks—that’s already in place. As a result they can implement programs more cost-effectively, using a greater proportion of funds for services within the community. To be clear, both CBOs and INGOs need to invest in overhead, but with CBOs, operating costs are typically much less than an INGO and are invested in local civil society.

- As a recognized part of the community, CBOs have a sophisticated understanding of local needs and power dynamics, and are often seen as more trustworthy by community members than outside agencies or foreign organizations.

- Unlike outside organizations who withdraw from an area when funding ends, local organizations remain in their communities. This means that direct funding into CBOs builds civil society in that area and in the country as a whole in a sustainable way. By working directly with CBOs, philanthropists are supporting local entrepreneurship—ideas for and by local people, built and delivered within the community marketplace.

To operate effectively in low-resource environments, CBOs must be immensely resourceful. This makes them particularly well-suited to working with private philanthropists, who are less constrained by the rules and practices of INGOs or bilateral donors. This kind of flexible support from private philanthropy allows CBOs to take risks, and to address issues and challenges more quickly than INGOs and outside agencies. Private philanthropists are also better able to fund capacity building, providing training and education for local partners that enhances their ability to tackle important priorities and operation gaps.

With so much to recommend them, why do so many philanthropic investors overlook community-based organizations?

In our experience, despite their knowledge and value, local organizations face several challenges in attracting international investors:

- Local NGOs are perceived as having higher risk for corruption and fraud than INGOs or domestic organizations.

- Small CBOs may lack the systems or infrastructure required for meeting the reporting standards of international donors, particularly in terms of financial management.

- Prospective donors may be apprehensive about partnering with an organization in an environment constrained by weak economic, social, or political systems.

- Small local organizations may not be able to absorb large grants or accept complex contributions.

- Many donors interested in international philanthropy don’t know how to identify high-performing CBOs or grant to them effectively.

Negative assumptions about developing-world NGOs are often rooted in perception rather than reality. European and North American donors often have expectations for financial management and auditing based on their own operating environments. A CBO, in contrast, is accustomed to its own local environment. Its staff may not be trained in reporting to an international audience, or in the style of an INGO.

Ironically, this culture clash underscores a different reality. CBOs, as local actors, are aware of the ways in which individuals in their community can commit fraud, and they know how to manage against it. Outsiders lacking the local perspective may not understand or appreciate the value of the fraud preventions that a CBO already has in place, and wrongly interpret the lack of familiar systems as a lack of proper controls or a lack of systems altogether.

To maximize returns and minimize risk in working with local organizations, Geneva Global employs a portfolio model. In this approach, philanthropic investments are coordinated under unifying themes. Within the portfolio, our clients can then invest strategically by funding a number of local and national organizations working on a given issue, and get them to collaborate.

Within the portfolio, one theme could be an anti-slavery initiative, for example. The initiative can bring together 10 or 20 organizations in neighboring countries to create cross-border networks which can deliver prevention work in “source” areas while simultaneously doing rescue and recovery work in “transit” and “destination” areas. The CBOs can collectively share best practices and help each other with practical considerations like navigating complex repatriation laws or ensuring that survivors receive appropriate follow-up care.

Investing directly with CBOs allows each organization to work to their strengths while still having access to the expertise of the larger group. The clustering approach within the portfolio thereby builds up local civil society by supporting each participating organization and the group’s collective power to tackle entrenched issues.

A portfolio model also reduces the risk of program failure, which may seem counterintuitive given the higher number of organizations involved. But just as a diversified portfolio—comprising both stocks and bonds, domestic and international holdings, liquid and illiquid assets—allows an investor to generate returns despite market fluctuations, a diversified philanthropic portfolio minimizes the impact of a single failure.

If one or two partners underperform, or there’s evidence of financial mismanagement—either due to fraud or just lack of accounting capacity—astute program management can adjust, focus on lessons learned, and carry on rather than throwing in the towel and closing down.

Misconceptions about local organizations make CBOs a tremendously undervalued investment opportunity.

Philanthropists who are willing to go beyond the traditional “safe” choices can generate extraordinary results: a relatively small investment with CBOs can generate large social returns, which then compound over time.

On behalf of one long-term client, Geneva Global has managed more than 1,400 projects with CBOs. These partnerships have helped implementing organizations act quickly in testing and scaling up new approaches, and they have allowed our client to be at the forefront in championing innovative ideas.

Moreover, by our calculations, these local investments have reached more than 21 million people around the world, demonstrating what is possible when philanthropic investors are willing to take on managed risk with a “think globally, act locally” perspective.