Learning from each other

After following the same path in academia for over a decade, I took a turn at a crossroads and became a philanthropy advisor at Geneva Global.

For the first few years in this new role, I tried to close the door between that “past life” and who I was becoming. But the papers that fell between my footsteps as I walked away from academia now crinkle in my pockets. They pile among other breadcrumbs that spill back to the past and into the future, mapping to who I’ve been and leading to points yet unknown. Daughter, student, teacher, translator, scholar, mother. I do my best work when I embrace all of the pieces that make up the advisor I am today.

And I improve by learning from colleagues who similarly bring the full breadth of their many backgrounds and selves to the job.

On our team at Geneva Global, we’ve co-created a space for this kind of peer learning through the conscious cultivation of a culture of clear communication, openness, kindness, respect, and acceptance. We have multiple internal channels where anyone — regardless of position or seniority on the team — can ask questions, start discussions, and source and share resources and ideas. A commitment to continuing education (including formally through individual staff professional development budgets) and the free exchange of ideas are intrinsic to who we are as a B Corp — learning is central to how we work.

The value we place on knowledge exchange — as well as on each other’s experiences and specializations — fosters innovation and creativity and facilitates deep collaboration. The informal peer learning community that binds our formal team of philanthropy advisors benefits us, and it also benefits our clients.

And we are not alone on our small but mighty Geneva Global team. Peer learning communities are flourishing across the philanthropy sector. Roots find purchase in common ground — around a shared cause, mission, or identity — sometimes, or often, in unexpected places. They can and do bloom into new and powerful ways of giving. But, despite their variety, the most vibrant communities often thrive in the same bright light; they grow best by nurturing, together, the individual richness of experience each member brings to the community.

What is a peer learning community?

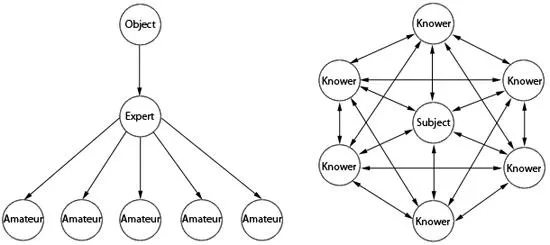

Peer learning in all forms is invaluable in advancing philanthropy. Communities can take many shapes. What binds them is the peer connection and a commitment to facilitating the free flow of knowledge between members, in all directions. Parker Palmer’s visual representation of decentralized expertise, seen on the right side of the graphic below, illustrates how peer learning works, in contrast to more traditional models of hierarchical knowledge sharing, shown on the left.

Parker Palmer “The Courage to Teach” (1998)

Peer learning communities accelerate innovation by creating a space for members to learn from, with, and alongside one another. Within philanthropy, some of these groups offer opportunities for donors and grantmaking institutions to connect. Others host giving circles or centralized grantmaking portfolios. And the philanthropy staff and advisors that support funders are also increasingly creating their own dedicated peer spaces to ask questions and share learnings and resources.

How do philanthropists and other private funders find their “peers”?

Even just among philanthropists and private funders, peer learning communities can look very different as they come together, growing to fit the populations they serve, as well as what they hope to accomplish. In our own work, we are seeing enthusiasm for peer networks. But a network can be big or small; informal with unstructured channels for sharing guidance and conversation; more formal with structured knowledge sharing opportunities, like site visits, workshops, and resource libraries; or even a bespoke combination of these elements.

The most generative communities of philanthropists and other private funders often take a shared identity or purpose as their starting point. These may include:

- A geography made common through origin, choice, or business interest (Circle Network, Asia Philanthropy Circle, AVPN, Philea, Giving Pi).

- An indivisible part of the self with a communal history of marginalization, like race or gender (Donors of Color Network, Women Moving Millions, Women Donors Network).

- A joint concern for how to do the most good, as via a distinct philosophy, model, or funding mechanism (Blue Meridian, The Audacious Project, Co-Impact, Resource Generation).

- A shared passion for directing resources toward a specific group, such as a religious community or other population (The World Congress of Muslim Philanthropists, Jewish Funders Network, International Funders for Indigenous Peoples).

- A collective focus on addressing an issue or challenge, from climate change to gender equality (Africa Partners Initiative, AVPN Gender Equality Platform, Oceans 5, Maverick Collective).

The doorway to entry may be wide or narrow, well-marked or only distinguishable with a map, passed hand-to-hand to new members over time. Regardless, this common starting point creates the initial conditions for connection and trust: essential ingredients of community building, no matter what form it may take, and vital groundwork for fostering peer learning. Members must feel welcome to show up as both learners and educators.

What kinds of peer learning communities are advisors and other philanthropy professionals building?

Among philanthropy advisors, we’re also seeing an increase in the development of communities for knowledge sharing, like peer networks (P150, Daylight Advisors).

- Some are currently and consciously working to grow their memberships, stretching across more geographies and sectors, as well as more deeply into them, to enrich their capacity for exchange and learning — and, in turn, strengthen the sector.

- Broader umbrella groups of philanthropy professionals may cast a wider net and convene practitioners with a wide range of specialties under a common mission or purpose (United Philanthropy Forum).

Similarly, intentional communities of practice, whether within organizations or across them, create a space for conversation on the best ways of doing certain kinds of work and other knowledge sharing (Emerging Practitioners in Philanthropy, Philanthropy Network, Human Rights Funders Network, East Africa Philanthropy Network). Like the philanthropist peer learning communities described above, communities of practice are typically founded around a shared focus, such as approaches to equitable grantmaking.

Why join a peer learning community?

Connect and learn alongside others, sharing insights to accelerate innovation

- Philanthropist networks can connect members just starting to think strategically about their giving with established philanthropists granting through their own foundations or already managing a robust portfolio of investments. They can also create spaces for vulnerability where even well-known philanthropists can exchange lessons learned and find new ways of giving.

- Among advisors and other philanthropy professionals, bridging backgrounds can create new perspectives on even the most intractable development challenges and may spark novel approaches for engaging philanthropists and other donors. Communities of practice advance and articulate guidelines and guardrails, improving and distributing knowledge on the most ethical and impactful approaches to grantmaking and other pathways to giving.

Mitigate funding risks through collaboration — and amplify impact

- Healthy philanthropist peer learning networks often organically encourage co-funding and other kinds of collaborative giving, lowering the individual financial risk of learning-by-doing while offering a pathway to much higher potential impact than giving alone. (Note that there are also numerous standalone funds and other kinds of pooled funding mechanisms that offer many of the same benefits of networks, sometimes without the element of deliberate peer-to-peer learning: The END Fund, Global Polio Eradication Fund, Africa Visionary Fund).

Unite to scale lasting social change

- More broadly, peer learning communities can serve as the building blocks for coalitions, task forces, movements, and other initiatives focused on advocacy, which bring together distinct or overlapping spheres of influence to effect change — at the international, national, state, or hyperlocal level (Trust-Based Philanthropy Project, European Philanthropy Coalition for Climate, Philanthropy for Climate, Initiative to Accelerate Charitable Giving).

Should I create my own philanthropic peer learning community?

First, ask yourself: What are you hoping to gain from membership in a philanthropy peer learning community? Who would you like to learn alongside? A peer learning community that would meet your needs might already exist.

If it doesn’t, think about:

- Who are the peers you’d like to bring into community with you? What binds you?

- What are the qualifications for membership (e.g., geographic location, profession, net worth)? Will you cap the total number of members? Conversely, will you actively recruit?

- Do you want members to “commit” to the learning community, either by paying a membership fee or by signing a pledge?

- How will you administer your learning community? If you bring on staff, who will pay their salaries or hourly rate? Will you cover any overhead yourself, or will you ask members to pay an annual fee?

- Who will be responsible for organizing convenings, learning opportunities, and other touchpoints?

- If you decide at the outset or over time to establish a vehicle for collaborative giving, where will you host it? Who will steward it? Will membership require a minimum contribution?

Many of these are areas that can be explored, together, as you join peers to form your learning community. Co-creation and co-ownership can strengthen a foundation, bolstering it for future collaboration, as well as bracing it through moments of disconnect and abrasion.

Building philanthropy’s resilience

Peer learning can take so many different forms, even within philanthropy. But its success, especially in the long term, often rests on a common understanding: despite the often wide variation in members’ philanthropic experience, no one is an expert on everything. Everyone is a learner; everyone has a responsibility to grow the collective knowledge that makes each community — and the sector as a whole — stronger. And that gives me hope in philanthropy’s resilience — and its future.