This March, I joined my colleagues, Joshua Muskin and Abdechafi Boubkir, and more than a thousand educators, researchers, and practitioners from around the world at the Comparative and International Education Society (CIES) Conference in Chicago. Representing Geneva Global’s Education Team, I spoke on a panel about educational technology in resource-limited settings and spent the week reflecting on both the evolution of our field and the direction it’s heading.

Framed by this year’s theme, “Envisioning Education in a Digital Society,” the conference raised questions that continue to sit with me: What does it mean to build meaningful, inclusive education systems in a world increasingly shaped by AI, data, and digital platforms? How do we ensure those systems work for learners and educators in places where connectivity is limited, unreliable, or completely absent? How do we design programs that are responsive not just to technology but to the people using (or excluded by) it?

These questions were at the heart of the panel on which I presented: “Digital Promises and Analogue Realities: Educational Technologies in Resource-Limited Settings,” alongside Anne Breivik (Stromme Foundation).

Tewodros Aragie Kebede (NORAD), Cathrine Tømte (University of Agder), and chair Leslie Casely-Hayford (Associates for Change), we explored the growing opportunities and tensions posed by global narratives of digital transformation and the realities we navigate on the ground.

As conversations around AI, education apps, and platform-based learning take the forefront globally, the gap between what’s possible in theory and what’s effective in practice continues to widen. This is particularly evident in places like rural Uganda and Ethiopia, where Geneva Global works with out-of-school learners through the Speed School program. In these contexts, connectivity is limited, devices are few, and electricity is highly unreliable.

For this reason, Geneva Global has leaned into low-tech tools — e.g., SMS, WhatsApp, and Zoom webinars — that are accessible, scalable, and responsive to local needs. These tools kept our program’s teacher professional development going and supported parent engagement during Uganda’s two-year COVID-19 school closure. Encouraged by its impact, Geneva Global continues to use these tools to strengthen Speed School’s implementation today.

In this work, we’ve learned that meaningful digital transformation isn’t about the newest technology. Rather, it’s about designing for where people are, not where we wish they were. Furthermore, in resource-limited settings such as those in which we work in Uganda and Ethiopia, the digital divide is not just about infrastructure. It is also significantly more about inclusion, relevance, and equity. If we are truly to envision education in a digital society, we must ask: Who is being reached; who is being left behind; and what tools actually serve the work on the ground?

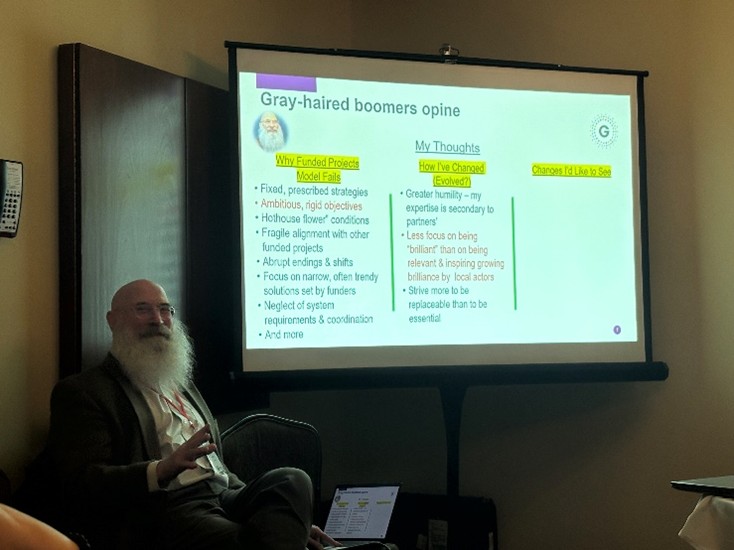

One of the more thought-provoking sessions I attended at CIES was a panel that engaged Geneva Global Managing Director, Joshua Muskin, in discussion with Joe DeStefano, formerly a Senior Director at Research Triangle Institute International, with moderation by Yasmin Sitabkhan, also from RTI. In a session they informally titled “Gray-Haired Boomers Opine,” the two long-time friends reflected on more than four decades of work in international education.

Josh’s reflections focused on three themes: why many education projects fall short; how his thinking has evolved over his career; and what it takes to build lasting change. He spoke candidly about the mismatch between short donor timelines and long-term systems change, the risks of chasing trends, and the importance of aligning with government priorities. He described how, over time, his role has shifted from one focused on offering solutions to a focus on supporting structures that can outlast him. “I’ve come to value being replaceable more than being essential,” he said. “Success means systems are stronger without us.”

Listening to this session felt especially impactful this year because the conference itself felt so different. Many familiar institutions and faces were missing. This included many who were intended to join the panel alongside Josh, Joe, and Yasmin. Their absence felt like a reflection of the current uncertainty across the international development landscape. Whether due to funding cuts, organizational shifts, or broader uncertainty, it’s clear we’re in a moment of change.

As someone still early in this work compared to Josh and his co-panelists, I’m struck by how much more we need to be thinking about resilience not just of learners and educators but of the systems and institutions doing this work. In our roles, sustainability isn’t just about scale. It is also critically about adaptability, humility, and building models that can hold up when tools, priorities, or funding shift.

As I left Chicago to travel to Uganda, then Ethiopia, I found myself thinking less about new tools and AI trends and more about what it takes to build education systems that can adapt, endure, and truly serve the people they’re meant to help.

For me, that means continuing to ask hard questions about what works, for whom, and under what conditions. It means paying close attention to the realities of the communities with which we work and supporting my colleagues in the countries where we work to design programs that respond first and foremost to those realities, not just to donor priorities or rigid project frameworks that often come predefined. It means as well staying open to change, even when the way forward isn’t entirely clear.

There’s no single answer to what education in a digital society should look like. But if there’s one thing I took away from this year’s conference, it’s that our best shot at getting it right will come from listening more closely, collaborating more honestly, and staying humbly grounded in the work that’s already happening on the ground.