Throughout my time at Geneva Global, I’ve had the privilege of learning about and supporting a host of community-based organizations (CBOs). These organizations have offered different strengths, whether in addressing slavery and human trafficking, improving the economic opportunities for underprivileged groups, or offering quality education to individuals who might not otherwise have access to school. Each of these organizations had different strengths, but they all shared an ability to connect with their communities, even while seeing possibility outside of current circumstances. They are innovative and effective, understanding the power dynamics and drivers of the issues they are addressing, and designing solutions that address the root causes and systems that enable the issue to persist.

Community-based organizations are critical to the localized work of shifting mindsets and behavior and are necessary for sustainable change. CBOs are proximate to the needs they seek to alleviate and interact regularly with their fellow community members to find innovative solutions to the problems within their locale. Often founded by visionary leaders, these local groups have experienced or witnessed the challenges they are addressing and are dedicated to improving individuals’, families’, and community wellbeing.

Community-based organizations are trusted by the community, as they are staffed by individuals from within the community and are consistently present in the community. As a result of these trusting relationships, the organization is also accountable to the community. Established in the community, the CBO can respond swiftly as the drivers and causes of an issue change or as a new emergency arises. The nimbleness, effectiveness, and connectedness of these groups allow CBOs to mobilize quickly. Given CBOs’ unique position in establishing change, Geneva Global has prioritized support to community-based organizations through financial and technical resources to assist with scaling up their work.

But CBOs cannot change the world solely on their own. Although critical to sustainable, local change, CBOs are just one stakeholder within a larger ecosystem to establish large-scale change. By definition, they operate at a local level. Their gains, while incredibly important, take place within a given community. Even when many different CBOs work together across districts or regions, those gains will stay isolated in localized pockets without linkages to the national or international level.

How can you bridge this gap? By deliberately bringing together a mix of partners.

There are many other actors required to establish systems change, including government leaders, policymakers, influencers, media, and large institutions, among others. Engagement with these actors is also necessary to establish social change.

At Geneva Global, our grant portfolios often include national-level NGOs in addition to CBOs. These national-level organizations typically enjoy greater name recognition due to the broader nature of their work and the more prominent level at which they operate. This name recognition opens doors to influence policy or to work with public figures. Many times, this name recognition has also brought increased funding, therefore the ability to hire additional technical capacity. These national-level players have the influence and capacity to establish positive momentum, but require the involvement of local CBOs to ensure strategic input into policy discussions that are relevant for the local community. By deliberately creating linkages between these efforts, we create a vehicle for collaboration and coordination that can take local solutions and amplify them up and out into the world.

Large national organizations can play a valuable role in systems change, particularly in partnership with a network of smaller local organizations. In my experience, a portfolio with a mix of large, well-established partners and smaller, leaner local organizations and advocates creates a tremendous opportunity for leveraging unique strengths. With their greater resources and capacity, established partners can provide technical assistance to newer or less formalized entrants. CBOs that cannot afford to have a legal expert or research guru on staff can access the specialized knowledge or expertise of the larger organizations. And large organizations with broad networks can connect smaller organizations with each other, creating a network with broader coverage and deeper membership.

In other words, grassroots organizations most often have the best solutions to local problems, but it’s the experience and reach of national or international organizations that can champion these solutions, creating linkages across communities, and sharing resources and learning across the wider movement.

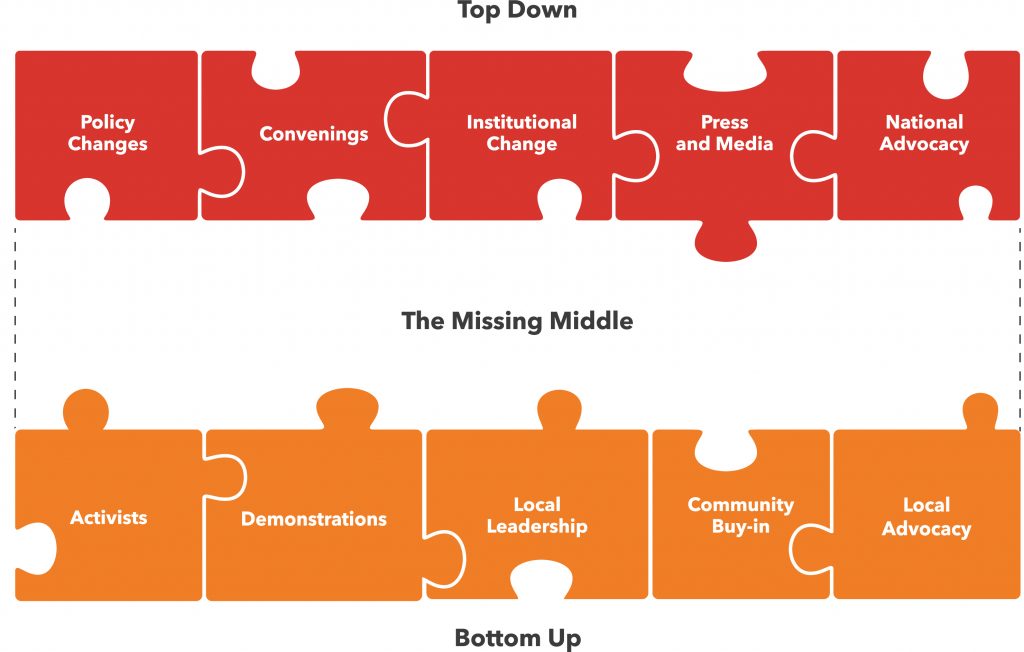

Creating linkages between local and national or international change agents is a critical component of systems change. In his explanation of the “missing middle,” our Chairman, Doug Balfour, wrote about the role of the systems entrepreneur acting as “the translator, the coordinator, the mediator, and the matchmaker” in effectively connecting top-down and bottom-up efforts.

These linkages serve a practical purpose; creating a real-time two-way conversation about what works that informs both policy and practice. On a given issue, change takes place at the local level. Local organizing is what changes social norms, embedding systems change at the ground level. In contrast, changes to the legal and policy systems take place at the national or international level. When the two-way conversation is working effectively, top-down structural changes are shaped by bottom-up local voices. Enacting change at the macro level, the top-down system then pushes these broad changes out across multiple levels, impacting the local systems in cohesive, coherent ways.

Collaboration between local and national organizations requires humility and patience. There are often vast differences between the capital city and the local community that can create divides between the two organizations. These differences impede collaboration if both entities are not willing to consider one another as equals with unique strengths to bring to the table. An independent facilitator can often help to translate information and perspectives to help parties work together and to remind all stakeholders of the power of collective will and common goals.

So how can you strengthen the impact of your philanthropy? Consider a mix of partnerships with unique strengths—and remember that collaboration takes hard work, grit, and perseverance, bridging the divide of perspectives and experience to strengthen the collective impact as diverse stakeholders work together. Through this collaboration and endurance, we might enact change at the local, national, and international level together.